Seven Tips to Perfecting the Rifle Standing Position

By Serena Juchnowski

Shooting a rifle from a bench or prone isn’t hard to master. More difficult is firing from the standing position. Becoming competent in this position not only makes you a more well-rounded handler of firearms, but if you compete, hunt or keep a rifle for home-defense, firing accurately from the standing position may be a necessary skill. I compete in a variety of rifle disciplines, so, for this column, I’ll focus on mastering the standing position for target shooting disciplines.

Yes, You Need This Skill

Competitive rifle disciplines place a significant emphasis on the standing position. Precision air-rifle shooters, for example, fire almost exclusively from the standing position, and match wins and losses often come down to a standing score. Other sports combine the scores of strings fired from standing, sitting and prone positions.

The basic standing position has two main forms, the supported and free-arm positions. The supported standing position, also called the “arm-rested position,” puts the elbow of the non-firing hand against the hip, using kinesthetics to help steady the rifle. The free-arm position is quicker to assume, with the shooter leaned forward and the arms out in front of the body. The non-firing hand grips the fore-end of the rifle while the firing hand pulls the stock tight into the shoulder.

Both positions have their uses, but the supported position is more stable over a longer period of time and, for new shooters, this is the preferred start to learning the standing position. The supported is also the steadier of the two and is used in collegiate-level rifle events. The free-arm position is more frequently used in action-shooting disciplines—3-Gun and IPSC, for example— in which the shooter is being timed and often moving in between banks of targets.

Even for those without competitive aspirations, shooting from the standing position is a skill that transfers into many different disciplines. Here are my top seven tactics to establish and perfect rifle fire from the standing position.

1. Triangles

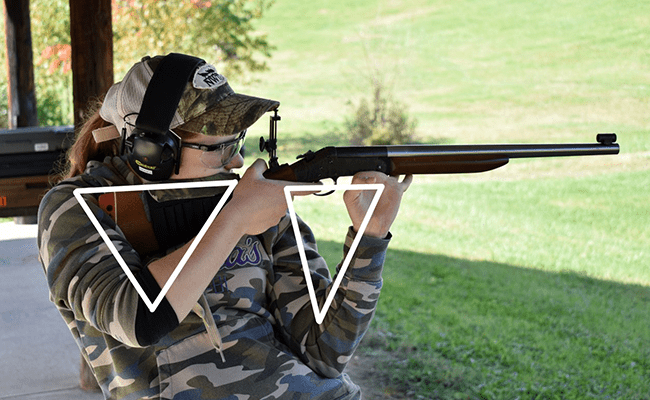

All shooting positions should be filled with triangles. Triangles are the strongest shape, and the more triangles one can make between their body and the rifle, the less wobble and movement there will be in the position. While this is simple to say, it is often difficult to self-diagnose.

In the supported standing position, the elbow of the non-firing hand should rest against the hip or slightly above it. Female shooters can often rest an elbow directly on the hip bone which provides optimum stability. With the rifle shouldered, the arm of the non-firing hand makes a triangle with the rifle held over top. Photo Credit: Max Crotser

Triangles play a role in stabilizing all positions, just with different anchor points. In the supported standing position, the shooter’s two legs make a triangle with the ground, the elbow of the nonfiring hand makes a triangle between the arm and the rifle, and another triangle is formed in a similar fashion between the arm and elbow of the firing hand and the buttstock. In the cross-legged sitting position, stability starts from the ground with each thigh and calf making a triangle with the thigh of the opposite leg. As in standing, the arms form triangles with the rifle, but with the elbow braced against the inside of the knees. In prone, the orientation of the triangles depends on if you are using a rest. If using a sling, two triangles form, stabilized on the ground, between the rifle and arms. If using a rest, one triangle forms between the rifle and arms, the other between the arm and the shooter’s chest.

2. Gun Fit

Rifle fit dramatically affects both a shooter’s accuracy and overall shooting experience. If, for example, a young girl is provided a rifle too heavy and long for her to shoot, she likely won’t enjoy shooting it and may become discouraged from practicing or going on to compete. So, does your gun fit you? Can you naturally and easily reach the trigger? Can you get your support hand in the proper position on the forearm to maintain the triangle needed there, or are you stretching that arm too far to keep from feeling like the rifle is nose-heavy? Can you properly and easily see the sights every time you shoulder the gun? “No” answers don’t necessarily mean you should run out and buy a new rifle (though that’s certainly an option), but you do need to get to “Yes” answers. That may include changing stock weight and length, optic or sight location or installing a new trigger that has a different reach.

3. Cheek Weld and Head Placement

Consistency in these two things is key. While most recognize that to fire an accurate shot everything has to happen the same way every time, it takes focus and lots of practice to get it right. When you’ve made a good shot, one where the bullet went exactly where you intended it to and one in which if felt like you had everything in the right position, you’ll want to focus on what it was that felt right and replicate it. How far was your nose from the charging handle, bolts or sights? Where exactly were your hands on the rifle when you broke the shot?

Standing is a critical stage of many competitive shooting events, including high power service rifle. Be sure to have a consistent cheek weld. With an AR-15, a consistent head position can be established by touching the nose to the charging handle. Photo Credit: Max Crotser

In perfecting your head placement behind the gun and your cheek weld on the stock, it’s important to remember to bring the rifle to you as you stand in your most vertical and supportive stance. When you bring your head to the rifle, leaning too far over as you do, you become unbalanced, with the fluid in the inner ear disrupted, which leads to extra wobble. Wobble does not make for accurate shooting.

4. Natural Point of Aim

When one takes any shooting position, the rifle naturally wants to end up in a certain spot. You can move or muscle the barrel of a rifle so that the sights are where you want them to be, but that approach is inconsistent and leads to bad shots and muscle fatigue. So, don’t fight the natural point of aim (NPA) by adjusting the gun. Instead, adjust your position so that the firearm points directly at the target.

To find your natural point of aim, mount your rifle, close your eyes and breathe. Open your eyes. If the rifle hovers over the middle of your target, your NPA is good. If your sights are lined up on another target or somewhere above, below or in-between, you should adjust your NPA. Almost always, the change is accomplished by moving your feet. Once you find your natural point of aim, do not move your feet again until you are done firing on that target.

5. Know Your Wobble Zone

Waiting for the rifle to stop moving and stay motionless on the target is an error that inflicts even the most talented offhand shooters. The rifle will never stop moving, but a solid, practiced standing position can limit that movement. Practice dry-firing or use a simulator like SCATT to observe the difference between where your shot is when you start to squeeze the trigger and where it ends up. Look for patterns and memorize the best point in your wobble zone to initiate the trigger squeeze.

6. Rest the Rifle

The standing position relies on muscle, so it never hurts to rest the rifle between shots on a stool or table (unloaded and in a safe position, of course). If the rifle is loaded and you are not comfortable taking the shot without a break, bring the rifle down in front of you with the muzzle pointed downrange. Rifle shooting is not a contest of who can hold their rifle the longest.

Do not be afraid to rest the rifle between shots. Two ways to do this are by unloading the rifle and cradling it your arm, muzzle pointed downrange, or by resting the rifle upright on a stool. The rifle MUST be unloaded if rested in an upright position. Photo Credit: Serena Juchnowski

Weight training can improve arm strength. Simply lifting your rifle into the shooting position (in a safe location with an empty chamber indicator inserted), holding it and resting it for varying lengths of time can help improve muscle memory and arm strength as well.

7. Follow-Through

Even if everything about your standing position is textbook perfect, little or no follow-through will destroy it. Be certain to carry every aspect of shooting—head position, cheek weld, body position, etc.— you have established through the end of the shot after you feel the recoil and the sights fall back on the target. This is especially important with slower moving bullets and longer barrels, where moving too quickly from the position will change the bullet impact.

It is important to maintain a stable position until after the rifle has recoiled. Photo Credit: Serena Juchnowski

Everyone has a different opinion on the best way to shoot standing, but the truth is that you must discover what works for you. What’s the position that affords you a comfortable shooting position, minimizes problems like rifle cant or sight alignment and results in consistent accuracy? As long as the position is safe, slight variations from person to person should be expected and are fine. If, however, practice is not resulting in consistent accuracy, then seek some guidance from an instructor, coach or even a fellow competitor. Sometimes it takes someone looking at you and your position to help you fix the things you can’t see.